Event/s

Jake Goldenfein: Computational Eugenics

Fri, 10. Aug 2018

6pm - 8pm

Over the past decade, researchers have been investigating new technologies for categorising people based on physical attributes alone. Unlike profiling with behavioural data created by interacting with informational environments, these technologies record and measure data from the physical world (i.e. signal) and use it to make a decision about the ‘world state’ – in this case a judgement about a person.

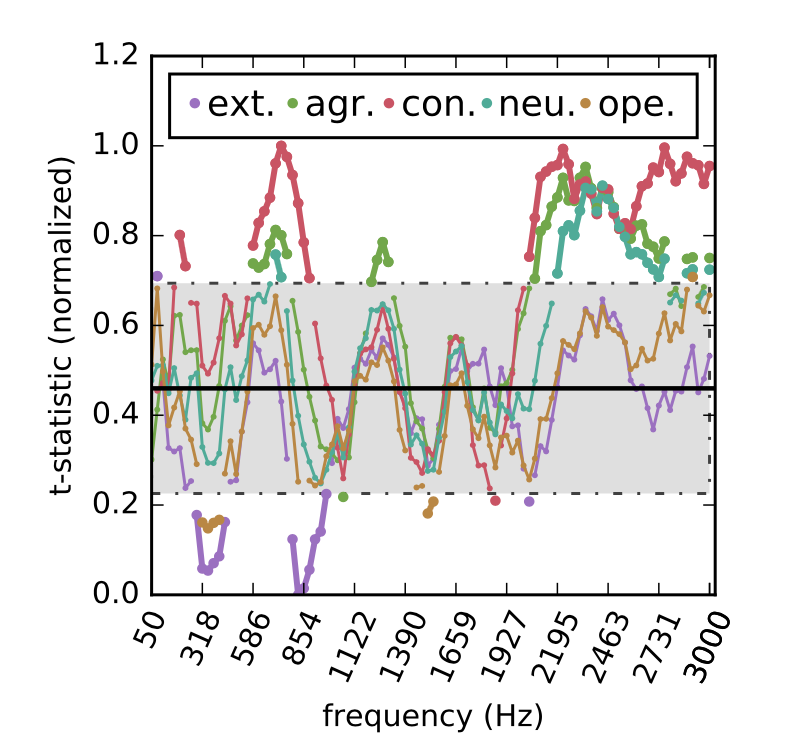

Automated Personality Analysis and Automated Personality Recognition, for instance, are growing sub-disciplines of computer vision, computer listening, and machine learning. This family of techniques has been used to generate personality profiles and assessments of sexuality, political position and even criminality using facial morphologies and speech expressions. These profiling systems do not attempt to comprehend the content of speech or to understand actions or sentiments, but rather to read personal typologies and build classifiers that can determine personal characteristics.

While the knowledge claims of these profiling techniques are often tentative, they increasingly deploy a variant of ‘big data epistemology’ that suggests there is more information in a human face or in spoken sound than is accessible or comprehensible to humans. This paper explores the bases of those claims and the systems of measurement that are deployed in computer vision and listening. It asks if there is something new in these claims beyond ‘big data epistemology’, and attempts to understand what it means to combine computational empiricism, statistical analyses, and probabilistic representations to produce knowledge about people.